- Home

- About

-

Programme

- English Phonics

- Cambridge English Assessment

- English Camp

- Branch location

- Franchise

- Testimonials

- News feed

- 中文 / Malay

You've probably seen the classic piece of "internet trivia" in the image above before - it's been circulating since at least 2003.

On first glance, it seems legit. Because you can actually read it, right? But, while the meme contains a grain of truth, the reality is always more complicated.

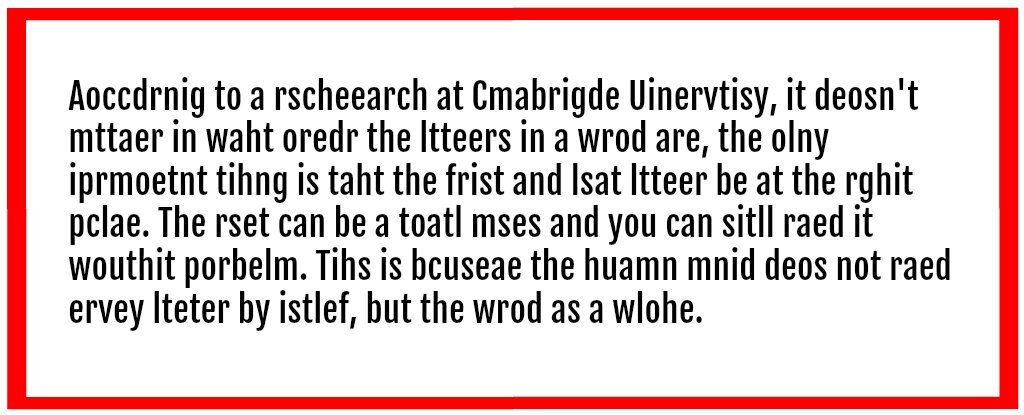

We've unjumbled the message verbatim.

"According to a researcher [sic] at Cambridge University, it doesn't matter in what order the letters in a word are, the only important [sic] thing is that the first and last letter be at the right place. The rest can be a total mess and you can still read it without problem. This is because the human mind does not read every letter by itself but the word as a whole."

A researcher named Graham Rawlinson, who wrote his PhD thesis on the topic at Nottingham University in 1976 conducted 16 experiments and found that yes, people could recognize words if the middle letters were jumbled, but, as Davis points out, there are several caveats.

1) It's much easier to do with short words, probably because there are fewer variables.

2) Function words that provide grammatical structure, such as and, the and a, tend to stay the same because they're so short. This helps the reader by preserving the structure, making prediction easier.

3) Switching adjacent letters, such as porbelm for problem, is easier to translate than switching more distant letters, as in plorebm.

4) None of the words in the meme are jumbled to make another word - Davis gives the example of wouthit vs witohut. This is because words that differ only in the position of two adjacent letters, such as calm and clam, or trial and trail, are more difficult to read.

5) The words all more or less preserved their original sound - order was changed to oredr instead of odrer, for instance.

6) The text is reasonably predictable.

7) It also helps to keep double letters together. It's much easier to decipher aoccdrnig and mttaer than adcinorcg and metatr, for example.

There is evidence to suggest that ascending and descending elements play a role, too - that what we're recognising is the shape of a word. This is why mixed-case text, such as alternating caps, is so difficult to read - it radically changes the shape of a word, even when all the letters are in the right place.

Stay in the loop with our monthly newsletter—discover exciting events and activities happening every month!

Stay in the loop with our monthly newsletter—discover exciting events and activities happening every month!

Stay in the loop with our monthly newsletter—discover exciting events and activities happening every month!

Stay in the loop with our monthly newsletter—discover exciting events and activities happening every month!